The following brief history comes from an undated brochure about the Wake-Brook House Books.

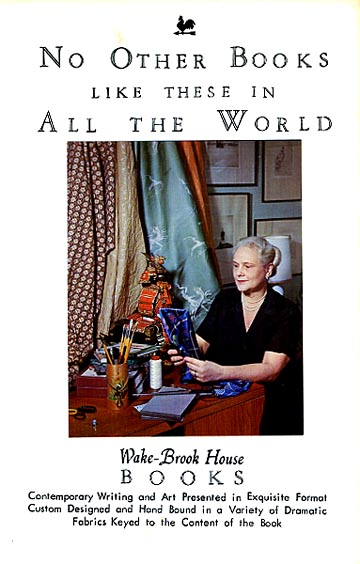

Cover Picture: Helene Geauque, head designer for Wake-Brook House in

her Miami studio. She has come to the designing of books by way of long

experience as a designer of costumes and stage settings. She approaches

the selection of type face, paper, and binding as she would approach the

creation of a series of costumes or sets. The whole must express the "character"

and the style and the dramatic mood of the text. The fabric she is draping on

a book board in the picture is a Chinese brocade woven in the caves of

Chungking during World War II.

The Story of Wake-Brook House

Almost daily letters come to us from new owners of Wake-Brook House books, asking three questions. “What is Wake-Brook House?” “Why have I only now learned of its existence?” “Do you have any descriptive literature concerning your activities and objectives which I can give to my friends?”

This brochure is an attempt to answer these queries.

Wake-Brook House was founded in 1946 with a triple goal, or ideal, if you like.

- To provide publication for writing of originality and exceptional literary merit, which lacks the mass sales potential necessary for acceptance by a major publisher. This is done without recourse to author-financing or author-subsidy in any form.

- To bring to discriminating readers, with confidence in their own critical judgment, work which is not solely keyed to mass appeal.

- To present this distinguished writing in a beautiful and enduring format, at a price anyone can afford.

Publishing has become big business. It is big in terms of the money involved and in terms of the numbers of books and magazine published annually. With this development, production, promotion, and sales costs have soared. All this being so, big publishing must operate on a coldly impersonal basis, with profit to the stockholders the controlling factor. This is as it should be, for money has a right to earn money. However, in this strictly commercial operation, only work which is sure of mass readership has a chance of publication. Writing which may be on a high level artistically but concerned with less popular subject matter, has relatively little likelihood of appearing in print simply because there is not sufficient market for it to offset a major publisher’s high costs and profit requirements. The alternative for the author is the so-called “subsidy” or “vanity” press, in one form or another, all too often.

Wake-Brook House was established in the hopes of ameliorating, at least a little, this unfortunate situation. We have been successful in modest degree, but there still remains a long way to go.

Our aim has been to discover means of making small editions practicable—in other words, self-liquidating. We insist that our efforts must return costs of production, sales, royalties, and so forth. We have searched diligently for ways to reduce costs without reduction in the quality of the finished product. Beyond that, Wake-Brook Is not profit-minded. Additional revenue beyond costs is channeled into two, to us, equally important areas.

- The discovery and encouragement of new talent in the fields of belles letters and fine arts.

- Development of what we have teamed “creative readership.” This is a body of readers who do not wish to have their minds made up for them, or their artistic horizons limited. This comprises the finest, strongest and broadest potential market for genuinely creative activity among writers and all other artists.

The original home of Wake-Brook House was a huge farmhouse in the foothills of the White Mountains of New Hampshire. It stood beside the road carved from the side of the mountain by order of the last Royal Governor, so his wife’s coach might move freely between Portsmouth and the summer palace by the lake. Construction on the house was begun in 1772, by veterans of the French and Indian Wars. The first unit was covered with lapped sheathing of boards three feet wide and tree-trunk-long. The second unit of the house was added in 1806, and it, too, was sheathed with three foot boards. These were not beveled and lapped, however, but were joined lengthwise by thin splines driven through grooves—the forerunner of modern tongue-and-groove. The façade of the enlarged building was decently covered with clapboards. Around 1850 another section was added, and the roof was raised, making a two-story-and-a-half structure along the Governor’s road. At the back, thanks to a high hillside basement of granite slabs, it was three-stories-and-a-half. The framework of the house was mortised and pegged, so it creaked and adjusted to the onslaughts of the rugged climate, like a ship accommodating to the stresses of the sea. There were five fireplaces—the largest eight feet wide, the smallest twenty-seven inches. Two had cooking cranes but the other three were for heating and conviviality. Paneling and mantels, like kitchen cabinets, showed the marks of hand-planes and carving knives. Handwrought thumb latches, paper-thin with use, controlled six panel doors. Water cam into the house and barnyard from a mountain spring by way of wooden water-pipes—great logs drilled lengthwise by a tree-long auger.

Here Wake-Brook House started publication, with hand set type printed on a foot-powered press. It specialized then, as now, in distinctive type faces, selected for compatibility with the text, and decorations available only through Wake-Brook House. Each book was, and is, considered as an identity, a personality. No two Wake-Brook House books are identical, and seldom even similar for type face, paper, lay-out and binding are keyed to the subject matter and style of the text.

Much of the work on Wake-Brook House books is done by hand. Skilled workers, after training in Wake-Brook House methods, fashion the books in their own homes. Printers, who are artist-craftsmen by inclination and commercial printers through necessity, find an outlet for their creative talents in turning out individual editions for Wake-Brook House. Weavers and printers of textiles, fabric dealers and importers, often supply experimental yardage for Wake-Brook House books. These fabrics range in type from homespun lines and wools through opulent silks suitable to Versailles and the important restorations here, like Williamsburg and the White House.

Hand-craft centers have been established in several sections of the country, and others are in process of development. Primary centers are in Sanbornville, New Hampshire; Carmel-by-the-Sea, California; Miami, Florida.

Hand-craft methods are only used, however, where they will contribute to the especial quality of a given book. Wake-Brook House is in no sense “artsy.” Where modern printing techniques and machinery can enhance the beauty of a book, and where the audience for the volume is substantial enough to justify heavy investment in long runs required by such methods, the finest mechanical facilities are employed. Frequently hand-craft and mechanical processes are combined in the development of a book, to create a distinctively Wake-Brook item. Sometimes editions are divided between a wholly handmade product for collectors, and a regular “trade” edition for store sale.

Ever since it started, Wake-Brook House has declared that there are “No books like these made anywhere else in the world.” This statement has never been challenged. They are designed to be works of art, yet they are durable. They are intended to be used freely—for intellectual stimulation as well as for the enjoyment of their physical beauty. They are meant to be cherished, and to encourage creative work in literature and the fine arts

Here Wake-Brook House started publication, with hand set type printed on a foot-powered press. It specialized then, as now, in distinctive type faces, selected for compatibility with the text, and decorations available only through Wake-Brook House. Each book was, and is, considered as an identity, a personality. No two Wake-Brook House books are identical, and seldom even similar for type face, paper, lay-out and binding are keyed to the subject matter and style of the text.

Much of the work on Wake-Brook House books is done by hand. Skilled workers, after training in Wake-Brook House methods, fashion the books in their own homes. Printers, who are artist-craftsmen by inclination and commercial printers through necessity, find an outlet for their creative talents in turning out individual editions for Wake-Brook House. Weavers and printers of textiles, fabric dealers and importers, often supply experimental yardage for Wake-Brook House books. These fabrics range in type from homespun lines and wools through opulent silks suitable to Versailles and the important restorations here, like Williamsburg and the White House.

Hand-craft centers have been established in several sections of the country, and others are in process of development. Primary centers are in Sanbornville, New Hampshire; Carmel-by-the-Sea, California; Miami, Florida.

Hand-craft methods are only used, however, where they will contribute to the especial quality of a given book. Wake-Brook House is in no sense “artsy.” Where modern printing techniques and machinery can enhance the beauty of a book, and where the audience for the volume is substantial enough to justify heavy investment in long runs required by such methods, the finest mechanical facilities are employed. Frequently hand-craft and mechanical processes are combined in the development of a book, to create a distinctively Wake-Brook item. Sometimes editions are divided between a wholly handmade product for collectors, and a regular “trade” edition for store sale.

Ever since it started, Wake-Brook House has declared that there are “No books like these made anywhere else in the world.” This statement has never been challenged. They are designed to be works of art, yet they are durable. They are intended to be used freely—for intellectual stimulation as well as for the enjoyment of their physical beauty. They are meant to be cherished, and to encourage creative work in literature and the fine arts